The Highs and Lows of Mental Health Care Class Action Litigation in Illinois Prisons

Alan Mills - Executive Director, Uptown People’s Law Center

“Compared to what it was before we started the case, this is heaven. But compared to what it was two years ago, I’m back in hell.” - Patrice Daniels, Impact Fund Class Action Hall of Fame Honoree

Patrice’s Story

The Joliet Treatment Center (JTC) was unlike any prison Patrice had been in. Instead of solitary confinement, JTC had group therapy. Instead of correctional officers, JTC had correctional treatment officers. The warden hung out in the gym and played games with the prisoners.

At first, Patrice was sure this was just another prison. But as the weeks went by, Patrice realized that JTC really was different. Officers were genuinely trying to get to know the prisoners. The administration practiced what it preached—the correctional treatment officers were the front line of the mental health program. They spent more time with prisoners than any other staff, and they alerted mental health staff when someone began to show the first signs of deteriorating. The mental health staff actually provided intense therapy when people needed it.

Patrice became a peer counselor and mentor.

Patrice became a peer counselor and mentor. He wanted to make the transition to JTC easier for new arrivals. When prisoners arrived at JTC, he made sure they knew what to expect. He assured them that this place really was different and they could get treatment here.

Along with a few others who were now JTC veterans, Patrice helped organize a patients’ council for prisoners to have a formal means of bringing concerns to the administration’s attention. When the deputy director came to meet with the council’s organizing committee, he was floored. He could not believe Patrice was the same person.

Patrice had not always been a leader. He had a horribly abusive childhood, and lived with undiagnosed schizophrenia for years. When he entered the prison system, he spent years cycling between solitary confinement and suicide watch, often so heavily medicated that he had no idea what was happening. When in solitary, he would hear voices. To silence the voices and confirm what was real, he would self-mutilate. His arms were literally nothing but scar tissue; scars criss-crossed the rest of his body.

At one point in a previous prison, Patrice began to bang his head against the wall to silence the voices in his head. A guard ordered him to stop, but Patrice wasn’t in touch with reality, and continued. He got a disciplinary report for “disobeying a direct order.” When some of the blood from his lacerated forehead splashed on the guard, Patrice was prosecuted for felony assault on a correctional officer, found guilty, and sentenced to an additional six years (on top of his life sentence).

Years of Litigation

In 2007, we filed Rasho v. Walker, a class action lawsuit challenging the way Illinois treated prisoners with mental illnesses. Patrice was one of the class representatives. The expert team hired at the beginning of the case concluded that Illinois prisons had no mental health system. They found just what Patrice (and many others) had experienced: mental health “treatment'' that consisted almost entirely of prescribing drugs, as well as isolating people with mental illness by putting them in solitary confinement for decades on end. Unsurprisingly, this did not help anyone with a serious mental illness, and many people continued to deteriorate.

Patrice’s letter to Alan, when things were starting to work.

In 2016, the parties entered into a settlement, which required the Illinois Department of Corrections (IDOC) to develop a meaningful treatment system. The treatment system established levels of care: outpatient, residential treatment units (RTUs), and inpatient, along with crisis care. The IDOC was also supposed to remove all crisis cells from solitary units, provide every patient with an individualized treatment plan, radically increase out-of-cell time, monitor medications and their side effects, account for mental illness when considering solitary confinement, and much more.

Over the next six years, Illinois made improvements. It opened four RTUs (including JTC), built an inpatient facility, provided a treatment plan for every patient, and increased the number of mental health staff. As Patrice found, the RTUs worked, at least for a while. Recognizing Patrice’s sacrifice in serving as a named plaintiff in the lawsuit, the Impact Fund inducted him into the Class Action Hall of Fame in 2018.

But while some progress was made, IDOC never came close to meeting the requirements of the settlement. It did not have enough staff. Too many people with mental illnesses remained in solitary, no meaningful treatment was provided to people on crisis watch, and it was never able to consistently provide the required out-of-cell time (among other failings).

As the RTUs began to fill up, correctional treatment officers were no longer part of the mental health team. Many new supervisors, who were transferred from traditional maximum-security prisons, brought their punishment-based culture to the RTUs. At the same time, staff shortages worsened, the number of treatment providers dropped, and the amount of time prisoners spent alone in their cells began to increase—none of which was good for anyone’s mental health. Patrice began to deteriorate. He spent most of the day struggling not to return to his old habits of self-mutilation. The total lockdown imposed by COVID only made matters worse.

The Prison Litigation Reform Act

The plaintiffs’ first and second attempts to force IDOC to implement the settlement were unsuccessful. Both times, the court held that the defendants should have more time to reach full compliance with the agreement. Then, as plaintiffs were preparing to bring a third motion to enforce the settlement, defendants—for the first time—argued that the settlement agreement was not enforceable at all, citing the Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA).

Under the PLRA, all settlements are divided into two categories: consent decrees and private settlement agreements. Consent decrees are agreements that must specifically address a constitutional violation, and the court retains jurisdiction to enforce the agreement. Meanwhile, in private settlement agreements, the court has no power of enforcement.

We believed we were being creative with our settlement agreement because the plaintiffs, the defendants, and the judge all believed that the settlement was a private settlement agreement. With this, we wouldn’t need a constitutional violation to be found, to which we thought IDOC would never agree.

In 2022, defendants unexpectedly reversed course, and argued that the settlement was not (as everyone had heretofore agreed) a private settlement agreement; rather, it was a consent decree because the court retained jurisdiction. However, defendants argued, since the settlement did not have the required constitutional violation, it also was not enforceable as a consent decree. In other words, it was a settlement which could not be enforced at all.

An Unjust Outcome

After months of briefing and argument, the trial court agreed with IDOC, and found that the settlement was neither a consent decree nor a private settlement agreement. The court thus returned the case to trial. The Impact Fund helped fund updated expert reports, which only confirmed that the system—after more than a decade of litigation—still did not provide meaningful treatment to Illinois prisoners with serious mental illnesses.

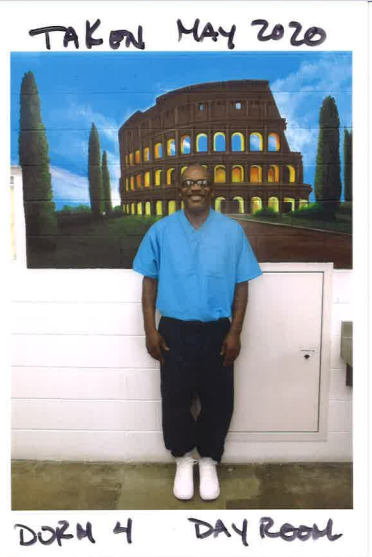

UPLC staff member Maurice Hughes, himself formerly incarcerated, drew this to depict the lack of mental health care in US prisons.

Then, as the experts were preparing their reports, the judge entered a new order: he directed the parties to address whether he had jurisdiction over the case at all. Again, months of briefing and argument followed. On October 23, 2023, the court found that it did not have jurisdiction. In sum, the judge held that although the settlement could not be enforced and was neither a consent decree nor a private settlement agreement, it nonetheless was a settlement. The judge thus disposed of the case, even though it gave the plaintiff class no rights at all. The court dismissed the case as settled.

The PLRA was supposed to curtail frivolous lawsuits. However, as Rasho illustrates, it also impacts cases which not only have merit, but in which plaintiff-prisoners actually prevail. It lays traps for lawyers—even the highly experienced lawyers on the Rasho plaintiff team, which included two attorneys with over 30 years’ experience litigating civil rights cases, and two other attorneys with over a decade of experience with prisoners’ rights cases.

But Undaunted, We Continue to Champion the Cause

Despite this outcome, we are committed to continuing the fight. We have appealed the dismissal of the original case and are preparing to file additional litigation challenging Illinois’ failure to provide meaningful mental health care to people in prison. Patrice’s transfer to JTC quite literally saved his life. We hope to see similar outcomes for all prisoners with mental illnesses in Illinois, who continue to suffer needlessly every day.